You love your grandma’s homemade sandwich bread recipe, but wish it was just a bit more tender and less crumbly. You’ve found a recipe online for cinnamon rolls but are bummed at how quickly they harden up and become dry once they’re out of the oven. Want to make your favorite yeast bread and rolls reliably soft and tender? Tangzhong is the solution.

With origins in Japan's yukone (or yudane), tangzhong is a yeast bread technique popularized across Asia by Taiwanese cookbook author Yvonne Chen. It involves cooking a portion of the flour and liquid in the recipe into a thick slurry prior to adding the remaining ingredients, resulting in soft, fluffy bread.

This pre-cooking accomplishes two positive things: it makes bread or rolls softer and more tender, and extends their shelf life. For the science behind this, read our Introduction to tangzhong.

If you’ve tried our Japanese Milk Bread Rolls or Soft Cinnamon Rolls, you know how deliciously tender they are. And you’ve probably thought about trying tangzhong with some of your own favorite yeast recipes. Softer, moister dinner rolls? Nothing wrong with that.

So how, exactly, do you convert a standard yeast bread recipe to use tangzhong?

Thoughtfully.

Start by managing your expectations. Do you really want to pair tangzhong (soft, tender bread) with crusty baguettes or chewy bagels? That would be like making potato chips in a steamer: it goes against the nature of the beast.

It's important to choose an appropriate recipe: a yeast bread that’s inherently soft, tender, and light. Be it a white sandwich loaf or buttery dinner rolls, tangzhong will enhance bread’s texture, and keep it fresher longer.

Once you've chosen a recipe, you need to determine its hydration: the percentage of water (or other liquid) compared to flour, by weight. A dough’s hydration determines how stiff or soft it’ll be, and also influences how vigorously it rises. Finished loaves with low hydration are usually dense and dry; those with higher hydration, soft and moist.

To take a simple example, a recipe that includes 75g of water and 100g of flour has a hydration of 75%. Or here’s an example in American weights: a recipe using 1 cup water (8 ounces) and 3 cups flour (12 3/4 ounces) has a hydration of 63% (8 divided by 12 3/4).

Don’t have a scale? I highly recommend you acquire one, because trying the tangzhong technique without a scale requires quite a lot of extra effort converting volume to weight.

And by the way, if you're following an older recipe that most likely doesn't include ingredient weights, see our handy ingredients weight chart.

The typical sandwich bread or dinner roll recipe (like these Golden Pull-Apart Butter Buns) has a hydration level of around 60% to 65%.

But when you’re using the tangzhong method, you want your recipe’s hydration to be about 75%.

Why? Because when using tangzhong, some of the liquid in the dough is “trapped” by the pre-cooked slurry (the tangzhong), and thus plays no part in the dough’s texture; as far as hydration is concerned, it’s as if that liquid isn’t even there.

Let’s say your original recipe’s hydration is 60%. When you transfer some of its liquid to the tangzhong, the resulting dough will behave as if its hydration is much lower.

The dough will be stiff and dry, which can inhibit its rise and lead to dense, heavy bread.

So in order to wind up with dough that’s as soft and smooth as the original, you need to add more liquid initially.

Let’s convert this popular recipe to use tangzhong and see how it goes.

1 cup (227g) milk

2 tablespoons (28g) butter

2 teaspoons instant yeast

2 tablespoons (25g) sugar

1 1/4 teaspoons salt

3 cups (361g) King Arthur Unbleached All-Purpose Flour

What’s this dough’s hydration? 227g (weight of milk) divided by 361g (weight of flour) = 63% hydration.

But remember, in order to use tangzhong you want your hydration to be 75%: the liquid should equal 75% of the weight of the flour.

Do your arithmetic: 361g x .75 = 271g. So you want the amount of milk in the recipe to be 271g, not 227g. Result? You’ll add 44g additional milk to your recipe.

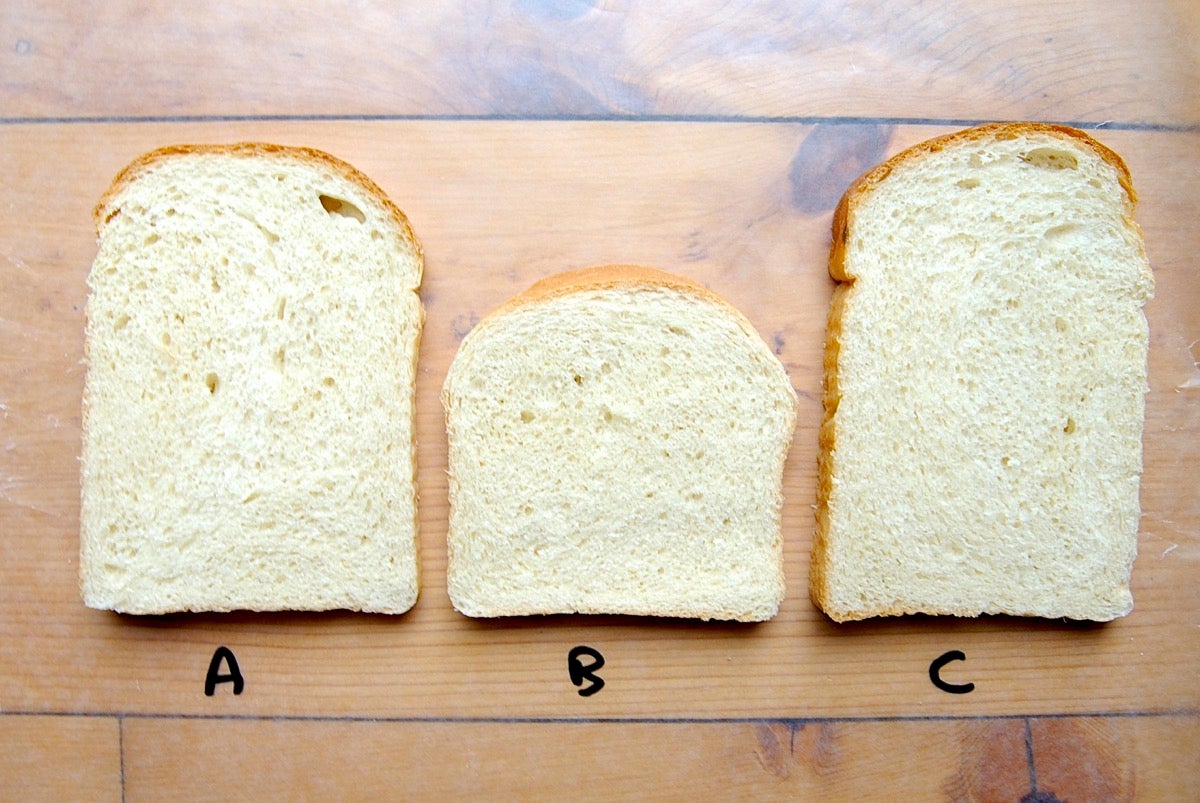

Let’s see how this works. I’ll make the recipe three ways:

(A), as written, with a hydration of 63%;

(B), using tangzhong without increasing the recipe’s hydration to 75%;

(C), using tangzhong after increasing the recipe’s hydration to 75% by adding 44g milk.

First I make the tangzhong slurry, the cooked mixture of flour and liquid. A standard slurry uses between 5% and 10% of the flour in the recipe and is composed of one part flour to five parts liquid (by weight).

I’ve now made this standard slurry often enough that this is what I use for any yeast recipe calling for between 3 and 4 cups of flour: 3 tablespoons (23g) of the flour in the recipe + 1/2 cup (113g) of the liquid.

Remember, you're using flour and liquid from the recipe, not adding extra flour and liquid! Take that into account when you're measuring out the remaining flour and liquid for the dough.

For each of the test loaves using the slurry (B and C), I combine 23g of the recipe’s flour with 115g of the recipe’s milk. I cook the mixture over medium heat until it thickens, and put it into the mixing bowl to cool down a bit while I assemble the other ingredients.

Next, I mix and knead the three doughs. (A), the control, is soft and smooth; (B), with the slurry but without any added milk, stiff and gnarly; and (C), with the slurry and added milk, very similar to (A), perhaps a bit softer.

I let the doughs rise, then shape them into loaves and place each in an unlidded 9" pain de mie pan (my loaf pan of choice). I let the loaves rise, then bake them.

Look at the difference! (A), the original recipe, and (C), the added milk/slurry recipe, (C), rise beautifully. (B), the recipe using the slurry but without any added milk, rises much less.

It’s impossible to photograph texture and moistness, but right out of the oven (C) is slightly moister and more tender than the original loaf (A). After a few days, (C), the loaf with the slurry, is still nice and fresh; while the original loaf is definitely showing signs of staleness.

Bottom line: By bringing your favorite sandwich bread or dinner roll recipe to 75% hydration and then using tangzhong in the dough, you’ll make bread that’s softer, lighter, more tender, and with longer shelf life than the original.

Once you feel comfortable with the basics of tangzhong, you can try fine-tuning your hydration math. While water is obviously 100% water, there may be other ingredients in your dough that are adding to its hydration: for instance, eggs or honey.

This fine-tuning is potentially only necessary in recipes that use a lot of butter and/or eggs, like brioche; or recipes with a significant amount of liquid sweetener.

Truthfully, most of my colleagues here at King Arthur consider simply the main liquid and flour when assessing a recipe's hydration. Because almost all of the time, that level of simplicity is fine: If your recipe includes just 2 tablespoons of butter, its minuscule water content isn't going to make or break your bread. Still, once you’ve got the calculator out, it’s fun to take this extra step towards accuracy.

If you want to drill down with hydration, here’s a list of common yeast bread ingredients and their percentage of water:

Milk: 87% water

Large eggs: 74% water (1 large shelled egg weighs 50g)

Liquid sweeteners (e.g., honey): 17% water

American-style butter: 16% water

Vegetable oil: 0% water (100% fat)

Use the information above to calculate how many grams of water are in any of these "rogue" ingredients in your recipe. Then add them to the total grams of the main liquid before calculating hydration.

A great variety of factors come into play when you're baking yeast bread, and some of these affect hydration. Keep the following in mind as you experiment with tangzhong:

Mashed potatoes or other mashed fruits/vegetables (pumpkin, squash) can affect dough's hydration. There's no way to judge their effect ahead of time; it's best to add them, then adjust dough's consistency with additional flour if necessary.

Hot/humid weather increases flour's moisture content; cold, dry weather makes flour drier. You'll typically use a bit less liquid in yeast recipes in summer, a bit more in winter; see our blog post, Winter to summer yeast baking.

Sourdough starter can be thick and viscous, quite thin, or anything in between. As with mashed vegetables, adjust the mixed dough's consistency as needed.

Have you tried baking yeast bread or rolls using the tangzhong technique yet? If so, how did you like the results? Please add your thoughts in comments, below.

For more on tangzhong:

Introduction to tangzhong: an intriguing technique for softer yeast bread and rolls

September 10, 2022 at 12:05pm

In reply to You have stated that a… by Joseph mlodzianowski (not verified)

Hi Joseph, we haven't experimented with this, but I suspect that you may get a little longer keeping quality, but not necessarily more softness in the overall baked good.

August 17, 2022 at 10:00am

I can't wait to try this method today! I'm also from New England. My sister graduated from, and is now a Professor at Brown University. Thank you so much for this article.

August 3, 2022 at 10:38am

Shouldn't we consider sugar when calculating the dough hydration? For example in sweet breads in which the sugar quantity is quite high

August 5, 2022 at 2:39pm

In reply to Shouldn't we consider sugar… by Giulia (not verified)

Hi Giulia, in terms of PJ's tangzhong conversion method, this isn't necessary. Sugar melts in a more complex way in baked goods, and the amount of water content added is more difficult to determine.

July 14, 2022 at 2:56pm

hi there, how do i determine the amount of tangzhong to prepare given a recipe? for instance, one with 200g of flour?

July 15, 2022 at 2:39pm

In reply to hi there, how do i determine… by cc (not verified)

Hi! A standard slurry uses between 5% and 10% of the flour in the recipe and is composed of one part flour to five parts liquid (by weight). Happy Baking!

June 19, 2022 at 6:43pm

I did all the conversions as described, I use jarred active dry yeast that I had just used to make a loaf of bread and it was fine. I made the adjustments so that I had exactly 75% hydration. The yeast bloomed okay. The only thing different was the use of Tangzhong. The first rise to double the size took 2 hours rather than the one hour it usually takes no more than one hour. The second rise didnt happen after the usual 20 minutes in fact after an hour it did rise a little but not above the pan edge. I baked it and it can only be classified as a total failer. Never even got that final little push rise when first putting it in the oven. Too bad because I really was hoping for a soft crust, close to store bought quality. Guess for me Tagzhong doesn't work. It's back to hard crust bread.

June 20, 2022 at 1:21pm

In reply to I did all the conversions as… by Frank (better … (not verified)

Hi Frank (aka Foodguru), we're sorry to hear that the tangzhong method didn't work well for you! It's hard to say exactly what went wrong, but if you'd like to contact our Baker's Hotline via phone or chat, we'd be happy to help you troubleshoot further. We're here M-F from 9am-9pm EST, and Saturday and Sunday from 9am-5pm EST, and the number to call is 855-371-BAKE (2253).

June 8, 2022 at 5:59am

These instructions are WONDERFUL! I’ve been baking a variety of breads for 40 years, 3 loaves at a time, including different dry ingredients and sweeteners as the spirit moved me, and just assumed the denser, drier loaves were always to be so. But tangzhong and these instructions for calculating ratios have given my bread a whole new, delicious quality. Thank you! Here’s ti lifelong learning!

June 6, 2022 at 12:32pm

I tried this today with 361g flour and 271g milk, with 23g flour and 115g milk for the paste. The dough is quite drier and stiffer than I would expect for a 75% hydration. Is this what is supposed to happen? Thanks

Pagination