You love your grandma’s homemade sandwich bread recipe, but wish it was just a bit more tender and less crumbly. You’ve found a recipe online for cinnamon rolls but are bummed at how quickly they harden up and become dry once they’re out of the oven. Want to make your favorite yeast bread and rolls reliably soft and tender? Tangzhong is the solution.

With origins in Japan's yukone (or yudane), tangzhong is a yeast bread technique popularized across Asia by Taiwanese cookbook author Yvonne Chen. It involves cooking a portion of the flour and liquid in the recipe into a thick slurry prior to adding the remaining ingredients, resulting in soft, fluffy bread.

This pre-cooking accomplishes two positive things: it makes bread or rolls softer and more tender, and extends their shelf life. For the science behind this, read our Introduction to tangzhong.

If you’ve tried our Japanese Milk Bread Rolls or Soft Cinnamon Rolls, you know how deliciously tender they are. And you’ve probably thought about trying tangzhong with some of your own favorite yeast recipes. Softer, moister dinner rolls? Nothing wrong with that.

So how, exactly, do you convert a standard yeast bread recipe to use tangzhong?

Thoughtfully.

Start by managing your expectations. Do you really want to pair tangzhong (soft, tender bread) with crusty baguettes or chewy bagels? That would be like making potato chips in a steamer: it goes against the nature of the beast.

It's important to choose an appropriate recipe: a yeast bread that’s inherently soft, tender, and light. Be it a white sandwich loaf or buttery dinner rolls, tangzhong will enhance bread’s texture, and keep it fresher longer.

Once you've chosen a recipe, you need to determine its hydration: the percentage of water (or other liquid) compared to flour, by weight. A dough’s hydration determines how stiff or soft it’ll be, and also influences how vigorously it rises. Finished loaves with low hydration are usually dense and dry; those with higher hydration, soft and moist.

To take a simple example, a recipe that includes 75g of water and 100g of flour has a hydration of 75%. Or here’s an example in American weights: a recipe using 1 cup water (8 ounces) and 3 cups flour (12 3/4 ounces) has a hydration of 63% (8 divided by 12 3/4).

Don’t have a scale? I highly recommend you acquire one, because trying the tangzhong technique without a scale requires quite a lot of extra effort converting volume to weight.

And by the way, if you're following an older recipe that most likely doesn't include ingredient weights, see our handy ingredients weight chart.

The typical sandwich bread or dinner roll recipe (like these Golden Pull-Apart Butter Buns) has a hydration level of around 60% to 65%.

But when you’re using the tangzhong method, you want your recipe’s hydration to be about 75%.

Why? Because when using tangzhong, some of the liquid in the dough is “trapped” by the pre-cooked slurry (the tangzhong), and thus plays no part in the dough’s texture; as far as hydration is concerned, it’s as if that liquid isn’t even there.

Let’s say your original recipe’s hydration is 60%. When you transfer some of its liquid to the tangzhong, the resulting dough will behave as if its hydration is much lower.

The dough will be stiff and dry, which can inhibit its rise and lead to dense, heavy bread.

So in order to wind up with dough that’s as soft and smooth as the original, you need to add more liquid initially.

Let’s convert this popular recipe to use tangzhong and see how it goes.

1 cup (227g) milk

2 tablespoons (28g) butter

2 teaspoons instant yeast

2 tablespoons (25g) sugar

1 1/4 teaspoons salt

3 cups (361g) King Arthur Unbleached All-Purpose Flour

What’s this dough’s hydration? 227g (weight of milk) divided by 361g (weight of flour) = 63% hydration.

But remember, in order to use tangzhong you want your hydration to be 75%: the liquid should equal 75% of the weight of the flour.

Do your arithmetic: 361g x .75 = 271g. So you want the amount of milk in the recipe to be 271g, not 227g. Result? You’ll add 44g additional milk to your recipe.

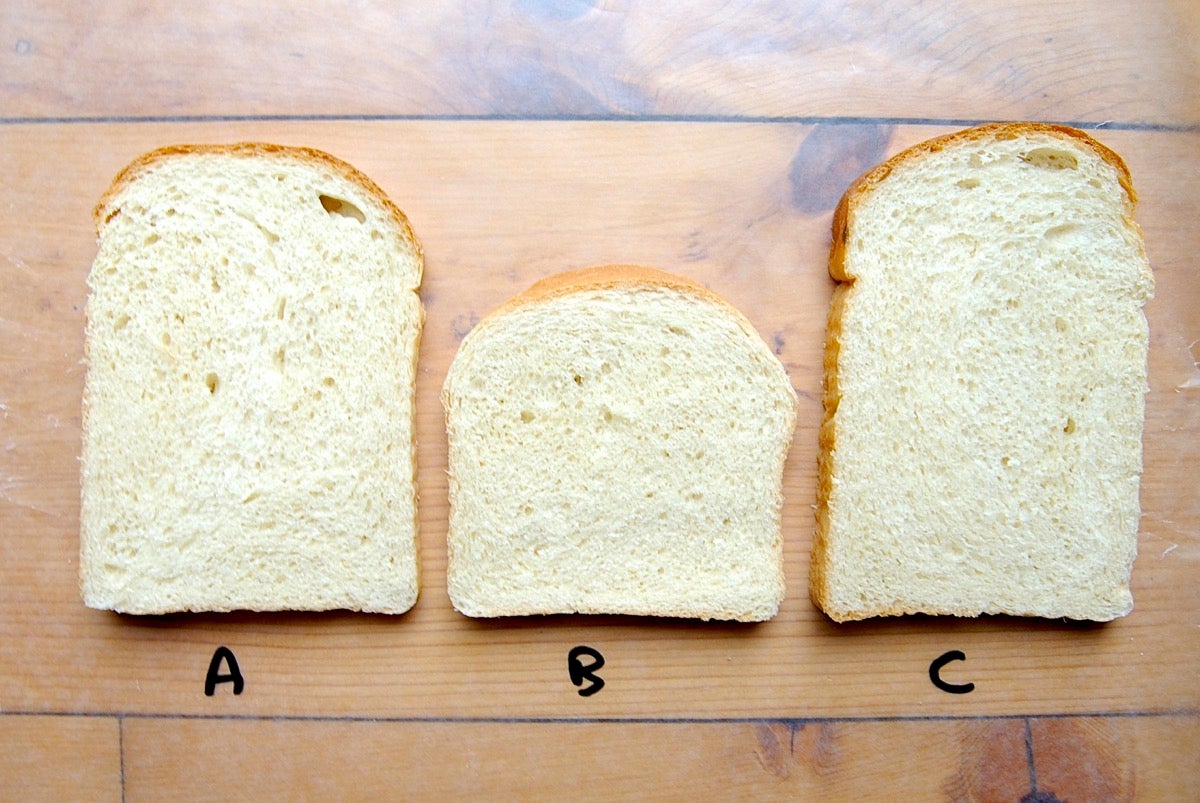

Let’s see how this works. I’ll make the recipe three ways:

(A), as written, with a hydration of 63%;

(B), using tangzhong without increasing the recipe’s hydration to 75%;

(C), using tangzhong after increasing the recipe’s hydration to 75% by adding 44g milk.

First I make the tangzhong slurry, the cooked mixture of flour and liquid. A standard slurry uses between 5% and 10% of the flour in the recipe and is composed of one part flour to five parts liquid (by weight).

I’ve now made this standard slurry often enough that this is what I use for any yeast recipe calling for between 3 and 4 cups of flour: 3 tablespoons (23g) of the flour in the recipe + 1/2 cup (113g) of the liquid.

Remember, you're using flour and liquid from the recipe, not adding extra flour and liquid! Take that into account when you're measuring out the remaining flour and liquid for the dough.

For each of the test loaves using the slurry (B and C), I combine 23g of the recipe’s flour with 115g of the recipe’s milk. I cook the mixture over medium heat until it thickens, and put it into the mixing bowl to cool down a bit while I assemble the other ingredients.

Next, I mix and knead the three doughs. (A), the control, is soft and smooth; (B), with the slurry but without any added milk, stiff and gnarly; and (C), with the slurry and added milk, very similar to (A), perhaps a bit softer.

I let the doughs rise, then shape them into loaves and place each in an unlidded 9" pain de mie pan (my loaf pan of choice). I let the loaves rise, then bake them.

Look at the difference! (A), the original recipe, and (C), the added milk/slurry recipe, (C), rise beautifully. (B), the recipe using the slurry but without any added milk, rises much less.

It’s impossible to photograph texture and moistness, but right out of the oven (C) is slightly moister and more tender than the original loaf (A). After a few days, (C), the loaf with the slurry, is still nice and fresh; while the original loaf is definitely showing signs of staleness.

Bottom line: By bringing your favorite sandwich bread or dinner roll recipe to 75% hydration and then using tangzhong in the dough, you’ll make bread that’s softer, lighter, more tender, and with longer shelf life than the original.

Once you feel comfortable with the basics of tangzhong, you can try fine-tuning your hydration math. While water is obviously 100% water, there may be other ingredients in your dough that are adding to its hydration: for instance, eggs or honey.

This fine-tuning is potentially only necessary in recipes that use a lot of butter and/or eggs, like brioche; or recipes with a significant amount of liquid sweetener.

Truthfully, most of my colleagues here at King Arthur consider simply the main liquid and flour when assessing a recipe's hydration. Because almost all of the time, that level of simplicity is fine: If your recipe includes just 2 tablespoons of butter, its minuscule water content isn't going to make or break your bread. Still, once you’ve got the calculator out, it’s fun to take this extra step towards accuracy.

If you want to drill down with hydration, here’s a list of common yeast bread ingredients and their percentage of water:

Milk: 87% water

Large eggs: 74% water (1 large shelled egg weighs 50g)

Liquid sweeteners (e.g., honey): 17% water

American-style butter: 16% water

Vegetable oil: 0% water (100% fat)

Use the information above to calculate how many grams of water are in any of these "rogue" ingredients in your recipe. Then add them to the total grams of the main liquid before calculating hydration.

A great variety of factors come into play when you're baking yeast bread, and some of these affect hydration. Keep the following in mind as you experiment with tangzhong:

Mashed potatoes or other mashed fruits/vegetables (pumpkin, squash) can affect dough's hydration. There's no way to judge their effect ahead of time; it's best to add them, then adjust dough's consistency with additional flour if necessary.

Hot/humid weather increases flour's moisture content; cold, dry weather makes flour drier. You'll typically use a bit less liquid in yeast recipes in summer, a bit more in winter; see our blog post, Winter to summer yeast baking.

Sourdough starter can be thick and viscous, quite thin, or anything in between. As with mashed vegetables, adjust the mixed dough's consistency as needed.

Have you tried baking yeast bread or rolls using the tangzhong technique yet? If so, how did you like the results? Please add your thoughts in comments, below.

For more on tangzhong:

Introduction to tangzhong: an intriguing technique for softer yeast bread and rolls

January 8, 2022 at 4:38pm

In reply to If my hydration is over 75%,… by Pina (not verified)

Hi Pina, adding a tangzhong starter to a sourdough bread recipe involves some other considerations; you may want to check out this blog post before you launch into this project.

December 15, 2021 at 11:22pm

Hi. Thank you very much for the article. I am wondering if the recipe also calls flour multi-grain including oatmeal (see below), do I count these into flour weight to calculate hydration as well? In addition, if I want to add chia seeds, how much should I add so it doesn't affect the hydration as chia seeds naturally absorb liquid? Thank you very much.

1/2 cup (60g) dry multigrain cereal mix or rolled oats

1 and 3/4 cups (410ml) boiling water

3 Tablespoons (45g) unsalted butter, softened to room temperature

3 and 1/3 cups (433g) bread flour

December 16, 2021 at 10:17am

In reply to Hi. Thank you very much for… by NW (not verified)

Hi there,

You'll really only count the flour amount when calculating your tangzhong, and adjust during the final dough for the other ingredients. Be sure to make small changes to one ingredient at a time and keep good notes.

December 3, 2021 at 6:03pm

This article helped me solve an issue with the Harvest Grains Bread recipe from this website. It's been my go-to sandwich bread for years, but the end of the loaf would frequently get pretty hard in about three days. I added the tangzhong roux to the dough, and four days later the last three or so inches of the loaf is still nice and tender. I didn't have to compensate too much for the fluid in the tangzhong because the recipe is nearly 80% hydration--unless I calculated that wrong...

December 4, 2021 at 11:57am

In reply to This article helped me solve… by Ellen Deffenbaugh (not verified)

Hi Ellen, it sounds like what you're doing is working well for you, so I wouldn't mess with success! Thanks for sharing!

November 22, 2021 at 4:27pm

PJ, you're a godsend. Thanks for this thoughtful and precise article! Can't wait to see if I can adapt my Portuguese sweet bread recipe and win over my family from the last 20 years of dry, overly-floured rolls.

November 19, 2021 at 12:46pm

Hi I need some help here in deciphering hydration level and what is the standard way of doing it. In the suggestion for incorporating Tangzhon into a soft bread recipe, to make it even softer and more moist (as above) I see you use milk and consider it all as water. The reason I am asking is because to make Hokkaido bread I sum all the water contents of each ingredient I use that can contribute water to the recipe.

gr whole milk x .88 = weight of water contributed to the dough by the whole milk

gr eggs x .75 = weight water contributed to the dough by the eggs

gr butter x .18 = weight water contributed by the butter in

gr honey x .18 = weight water contributed by the honey

gr water x 1 = weight of water

If I calculate hydration level not considering the water in milk (and other ingredients that I add in) like you do above, my Hokkaido recipe shows a hydration level of 77.9 If I adjust for water content of the ingredients in my recipe, hydration level comes out to 70%

Do I adjust hydration level considering water content of the ingredients or not? Either way you do it, I believe each person (over time) will adjust the recipe until he or she gets the "best" results. But when it comes to exchanging information between people, we need to calculate and express hydration level using a standard method common to all. And I am not sure if I should drop adjusting for water content according to type of milk, butter fat in butter, eggs, honey or Barley Malt syrup, etc, which as in this case I do use in my homemade Hokkaido bread!

November 19, 2021 at 3:50pm

In reply to Hi I need some help here in… by Dan (not verified)

Hi Dan, these recommendations are for converting a recipe to incorporate a Tangzhong starter. Since your Hokkaido bread recipe already includes this type of starter you shouldn't have to adjust the hydration in this way. I would stick with your recipe as written. If, on the other hand, you are converting a recipe that doesn't already include this type of starter then we would recommend calculating the total hydration (including the liquid content in butter, milk, eggs and liquid sweeteners) before determining how much extra liquid is necessary to add a Tangzhong starter.

November 20, 2021 at 7:37am

In reply to Hi Dan, these… by balpern

Barb Thanks for the reply! The recommendation been made on how to include Tangzhon in recipes that could benefit from its incorporation, is very good! Yes you are right, I am not "adjusting" my recipe, as the Tangzhon addition is already incorporated into it. I was just wondering why in the provided recipe, milk is considered 100% water?

November 20, 2021 at 9:46am

In reply to Barb Thanks for the reply! … by Dan (not verified)

I'm sorry I didn't understand your question the first time! According to PJ's figures milk should be considered 87% water, and you could certainly factor it that way when considering the overall hydration of your recipe in order to be more accurate. I think PJ deemed this "extra credit" because the math can be a bit daunting for some folks.

Pagination