Special occasions of all kinds are cause for cake. Graduations, birthdays, weddings, and parties for hellos or goodbyes almost always call for cake as the centerpiece of the dessert action.

Just about everyone I know likes eating cake. Baking it? That can be a different story.

Fortunately, cake is a pretty broad category, and there's a range of cake styles that can suit almost any baker's comfort level. I think my first cake was a pudding cake from the old Betty Crocker cookbook, called "Hot Fudge Pudding." I still make that cake. Warm, with good vanilla ice cream and the goo from the bottom spooned over it? Oh, yes.

As my culinary career developed, somehow I got into layer cakes. I enjoyed my pastry class at the Culinary Institute of America a lot. When I learned to clean up the top edge of a frosted cake by sweeping my spatula toward myself at just the right 45° angle, it was extremely satisfying. I relive that moment to this day, with every cake I make.

I'm still learning, though. (I'm at the stage where I know some things, but am realizing there's so much more that I don't know, and the deeper I dig the more complicated things can get). The quest? To understand cake flour, and what happens with different flours in the same cake recipe. Here's the lineup of contenders:

Bleached Cake →Unbleached Cake Flour Blend→Self-Rising→Unbleached Pastry→Unbleached All-Purpose

Bleached Cake →Unbleached Cake Flour Blend→Self-Rising→Unbleached Pastry→Unbleached All-Purpose

You probably know that different types of flour have unique protein levels. It's one of the quickest ways to get a bead on how it will bake. More protein = more structure and chewiness, which is good in bread dough, not what you're after in cake.

That said, the lower protein number should make the best cake, yes? That's what I set out to discover, making five different (actually seven, if you count the screw-ups) cakes, using the same formula and each of the flours you see above. We'll get to those results in a bit, but in the meantime, if you're wondering, here are their protein levels:

Softasilk bleached cake 6.9%→KAF Unbleached Cake Flour Blend 9.4%→Unbleached Self-Rising 8.5%→Unbleached Pastry 8%→KAF Unbleached All-Purpose 11.7%.

Before I go down this path, I should tell you I consulted at length with our own Dr. Andrea Brown, who not only reads but can translate scientific journals and milling science papers. After many hours of discussion, it was clear that while man has been grinding flour and baking with it for millennia, on the molecular level, there are lot of things we really don't know yet. We just know that some things work. Why is still a work in progress.

What does bleach do to flour? Guess what: It depends on the bleach. Different types of bleach are used on different flours. Bleached all-purpose flours can be treated with hydrogen peroxide, benzoyl peroxide, calcium peroxide, or azodicarbonamide. These bleaches take away electrons from gluten's two components, glutenin and gliadin (a process known as oxidation), and the resulting proteins formed in dough are somewhat stronger as a result.

Oxygen from the air also bleaches flour, but more slowly. The process of aging flour happens as it's stored in silos, eventually put into bags, and as it makes its way through the supply chain to your door.

Most cake flours are treated with chlorine bleach. Chlorine is much stronger than peroxides, and its interaction with all of the flour's components (starch, protein, fat) is still being researched. What we do know is that bleached flour is better able to form a matrix that can hold together a high-ratio cake.

What's a "high-ratio" cake? There are three things to look at in a cake's formula to determine this. A high-ratio cake meets the following qualifications:

The texture of a high-ratio cake is tender, moist, and usually close-grained without being heavy or gummy. Most classic wedding cakes are high-ratio formulas.

At the other end of the spectrum, a genoise such as you find in our Tiramisu or Bûche de Noël relies on whipped egg foam stabilized with flour for structure; to be moist it's brushed with simple syrup. Our Golden Vanilla and Pound cakes are somewhere in between.

Cake flour starts with low-protein flour, which means a greater percentage of the flour in your cup is composed of starch. It's also very finely ground, with a texture that feels silky. (This has more to do with the way the wheat berries shear as they go through the rollers than with any super-special sifting, FYI.)

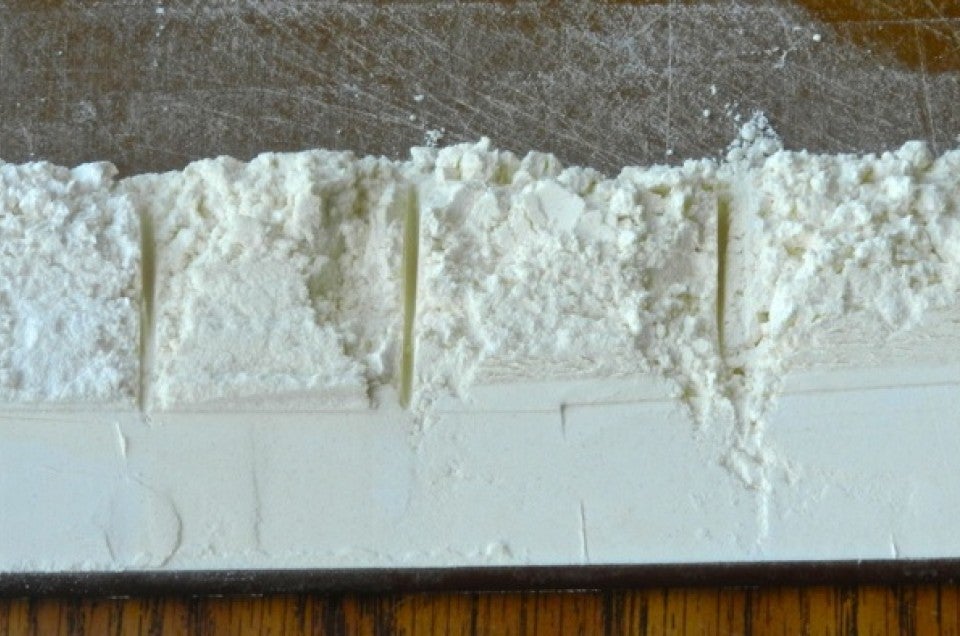

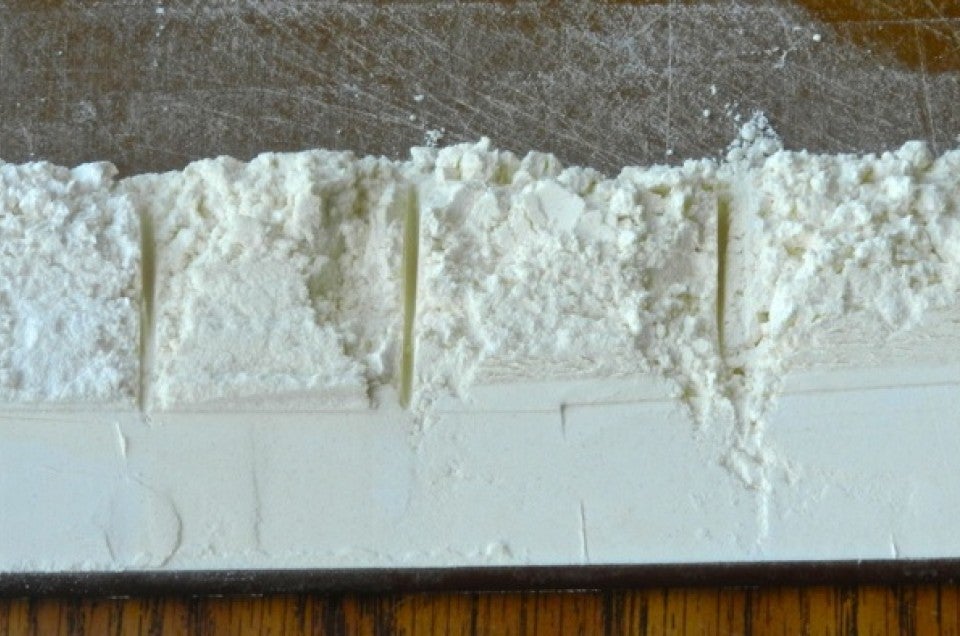

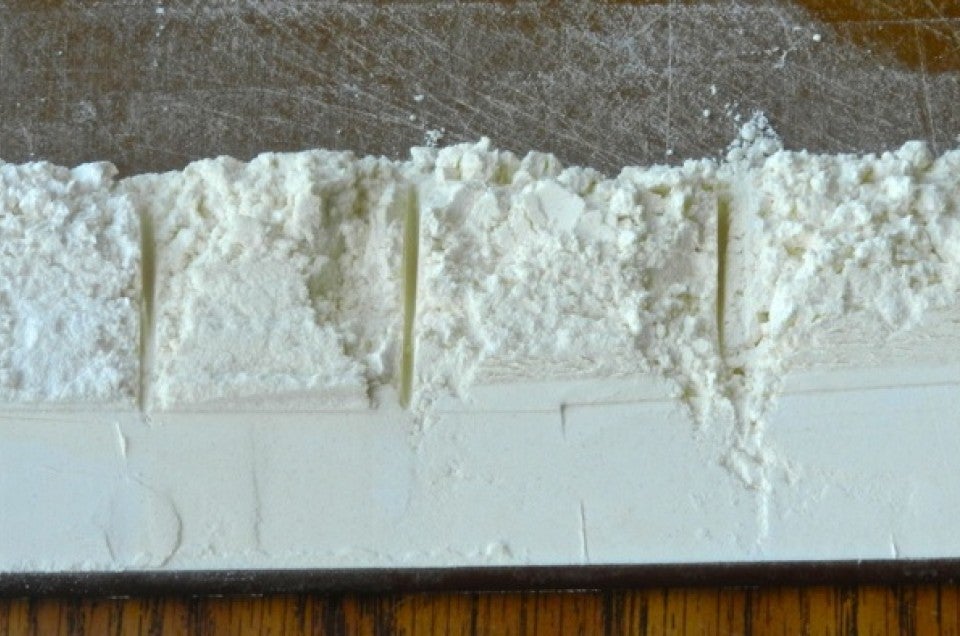

If you're trying to determine what kind of flour you have in an unmarked bulk bin, squeeze it and see what happens. Lower protein flours will stick together and make a clump in your hand; higher protein ones won't. This is one of the reasons cake recipes call for sifting dry ingredients (or whisking them through a strainer). It's the most effective way to blend them evenly.

The bleached cake flour (6.9% protein) was the tallest of the layers, with a very fine crumb. It was moist without being dense. The unbleached cake flour blend (9.4%) wasn't as tall, but the crumb was even and fine. The cake was a little more dense, moist, and tasty. Number three, our unbleached self-rising flour (8.5%), was the biggest surprise. It made an awesome cake (I adjusted the recipe, using an equivalent weight of self-rising to match the weight of cake flour that was called for, and leaving out leavening and salt, because those are already in the self-rising bag).

Here's where things get interesting. Number four in our lineup is our unbleached pastry flour (8%). If low protein makes good cake, what happened here? Dr. Brown and I tossed it around, and it came out that our self-rising flour has a more acidic pH than the pastry. Acid helps the proteins in the recipe's egg whites set, enhancing the structure and making a higher cake layer.

I've had this poor result with pastry flour in cakes several times; it's not the ingredient of choice for a high ratio cake. The pastry flour layers were the only set I threw out, not even considering giving them out as snacks. The cakes were low, gummy, and just not at all appealing.

When we were testing our Unbleached Cake Flour Blend, we had a similar result. I made what felt like a billion cakes, and then Sue Gray took the formula across the finish line. This was her output from just one day of testing the blend:

Last but not least, on the far right is the layer made with our unbleached all-purpose (11.7%). It's relying on the protein in the flour for more of its structure, so it's not quite as tender as the cake made with the bleached or self-rising flour; but it still looks good and tastes just fine.

Does the flour you reach for make a difference when you're going to make a cake? Absolutely. Do you need to buy a box of bleached cake flour to make cake? Depends.

For some bakers, the texture they want can only be achieved with bleached flour. For my money, I'd rather have our Unbleached Cake Flour Blend, or after what I learned with this project, our Unbleached Self-Rising Flour in my cake any day. Self-rising (self-raising in Britspeak) is the most common flour used for cake in England, and I'm now a believer, and will be giving it a spin in more cakes from now on.

I've been depending on and getting great results from our Unbleached Cake Flour Blend ever since we developed it. As I said before, there's a cake out there for every baker, and a lot of choices for flours. If you have a recipe you love and depend on that calls for bleached cake flour, and you're not in a pinch for time, you might want to try the alternatives I've experimented with and see what you think. You may stay with what you know, or maybe you'll find a new flour friend!

For more on the ins and outs of cake baking, please see our comprehensive Cake Baking Guide.