Pie crust — gotta love it, right?

Flaky and tender when you nail it, tough as rawhide when you don't, pie crust divides all of us bakers into definitive categories: those who succeed; those who fail, but keep trying; and those who buy Mrs. Smith's.

Why is pie crust so tough — often literally? Well, it's all about the fat, the water, and the flour. Three simple ingredients that, together, can create a masterpiece — or mayhem.

Flour does make a difference, but not as much as you might think. A lower-protein pastry flour, like our Pastry Flour Blend, will inherently make a more tender crust (and will also be a bit more fragile when you're rolling it out).

Truthfully, I use our all-purpose flour in my pie crust; I have to be careful not to work it too hard once the water is added (for fear of developing its gluten), but for me, it offers an ideal blend of good results and ease of handling.

Make it ice water. Simple enough, right? Sure, you can use milk, add an egg, and try other types of liquid, but water produces reliably good results — so why not?

Ah, now comes the ingredient that arguably makes or breaks a pie crust, and also creates the most debate:

Your grandma used lard. Your mom used shortening. You use butter. Are all fats created equal?

I decided to find out.

First thing I did was rule out lard. NOT BECAUSE IT'S NOT A PERFECTLY GOOD FAT AND CAPABLE OF MAKING WONDROUSLY TASTY PIE CRUST. After all, our ancestors made lard-crust pies for centuries and, like lard-fried doughnuts, they were delicious.

I'm ruling out lard simply because good, fresh lard isn't as universally available as shortening and butter. So if you love lard, and have a good supplier – stick with it.

But if butter and vegetable shortening are your choices, read on.

For years, I've alternated between two favorite recipes: Classic Double Pie Crust, a crust made with both shortening and butter; and All-Butter Pie Crust.

One Thanksgiving I'd go with an all-butter crust for my Apple Pie; the next, I'd make my Lemon Chess Pie with the shortening/butter clone.

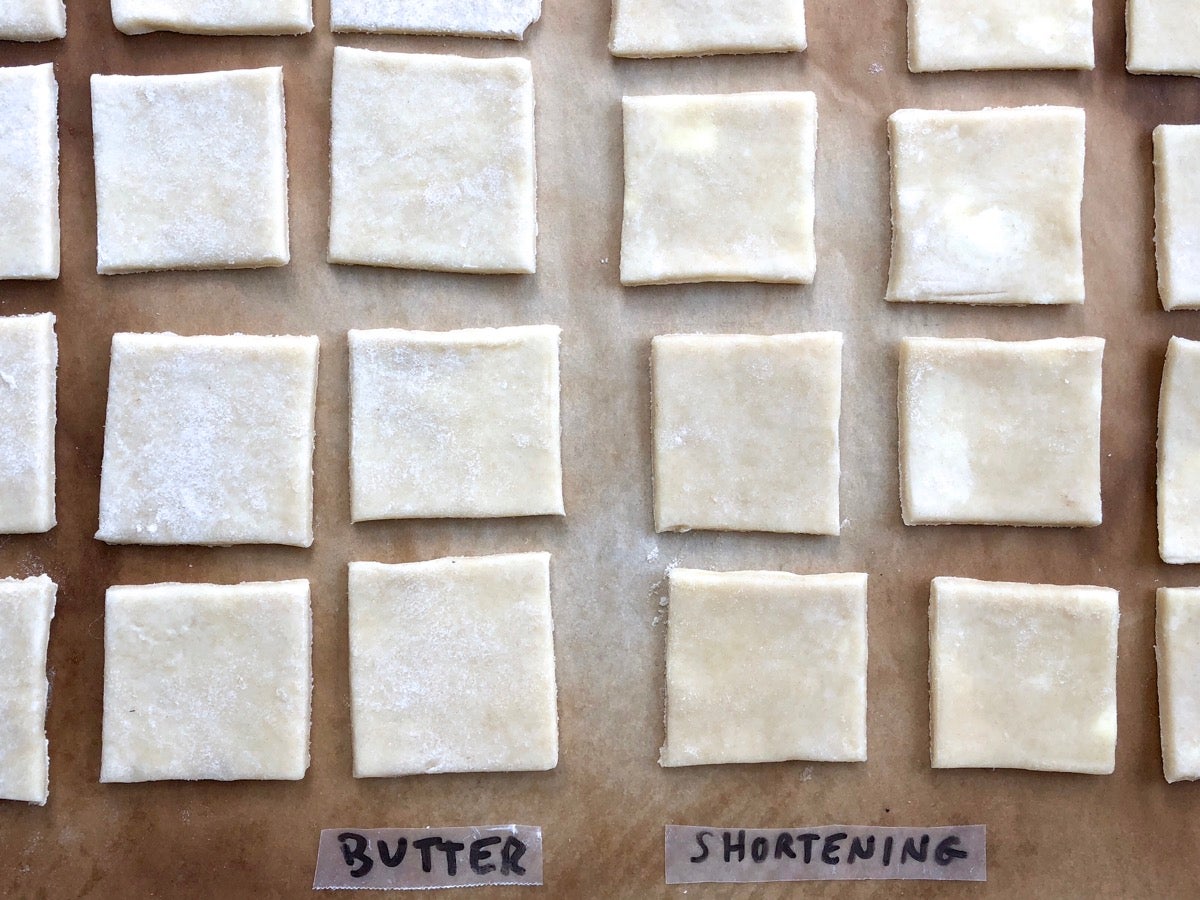

But never had I made both crusts in tandem, and done a side-by-side comparison. Which was flakier? Which tasted better?

This was the year. Having signed up to do a pie demonstration at a local bookstore, I decided I'd best practice both – at the same time.

And I made an amazing discovery (amazing to me; we pie geeks are easily amazed): something I'd always believed to be true was absolutely, categorically, without a doubt not true at all.

I'd always told people that a shortening/butter pie crust would have better texture than an all-butter crust, due to shortening's higher melting point. Why?

Fat keeps the layers of flour/water "matrix" separated as the pie bakes; the longer fat is present in its solid form (score one for shortening, with its high melting point), the more flakes will form, the more tender/flakier the crust will be.

Now, that may be true. I didn't actually count the number of flaky layers in each crust.

But one thing was abundantly clear: the all-butter crust (above left) made a lighter crust, with more defined flakes than the butter/shortening combination (above right).

I was totally puzzled until it dawned on me: butter contains more water than shortening.

As the crust bakes, that water is converted to steam, puffing up the crust (and its flakes) like someone blowing up a balloon.

And flavor? The all-butter crust tasted — well, buttery, of course. The butter/shortening crust (which was, by the way, just as tender and flaky as the butter crust, but without its light texture) tasted a bit like butter, and a bit like pie crust — that indefinable something that tells your taste buds, yes, I'm eating a piece of pie.

Both were good — just different. And one of the chief differences was looks: the butter crust produced a very ill-defined edge. My careful fluting basically went up in smoke (er, steam).

So if you're after looks, stick with the butter/shortening combination (or all shortening). If looks don't matter to you, I'd go with the all-butter crust.

While I was at it, I decided to test the famous Cook's Illustrated secret to tender, flaky pie crust: using vodka in place of half the water in the crust.

The theory is that vodka, being alcohol rather than water, will develop flour's gluten less than plain water, thus creating a more tender crust.

The verdict? I couldn't discern any difference in the flakiness/tenderness of the vodka vs. non-vodka crusts.

BUT the vodka crust rolled out more easily; with its silken, smooth texture, it was a pleasure to work with.

So would I add vodka to pie crust? Sure. I think I'll even keep a little bottle in the fridge, so it's handy for pie crust or a gimlet — whichever comes first!

OK, I've given you a map. And here you stand at the crossroads, ready to make a decision on the butter vs. shortening in pie crust debate.

Which will it be: Classic Double Pie Crust, or All-Butter Pie Crust?

May the best crust win!

For more handy tips and useful information on pie crust, check out our pie crust guide.

Note: This blog post focuses on the difference between shortening and butter in pie crust, without examining the relative health benefits of each. For health information concerning these fats, speak to a doctor or nutritionist.

September 11, 2017 at 10:48am

September 11, 2017 at 2:55pm

In reply to I only use lard for my pie crusts and they are nice and flaky!!… by MA Eglesia (not verified)

May 30, 2017 at 10:34am

May 28, 2017 at 5:13pm

May 28, 2017 at 10:10am

May 30, 2017 at 2:02pm

In reply to What about making good old fashioned ginger snaps. Will butter… by Clay Pendleton (not verified)

February 19, 2017 at 7:05am

December 18, 2016 at 10:13pm

December 20, 2016 at 2:58pm

In reply to It's 2016...I've read all the comments. I'm an RN of 30 years e… by May (not verified)

November 19, 2016 at 4:06pm

Pagination