I’m in love — with tangzhong.

This Asian yeast bread technique — which has origins in Japan's yukone (or yudane) and was popularized across Asia by Taiwanese cookbook author Yvonne Chen — enhances both moisture and keeping quality when applied to soft bread (think sandwich loaves, dinner rolls, cinnamon buns, and their ilk). You know how your homemade toasting bread starts to dry out and crumble after a few days? Or your cinnamon buns seem to harden up within just a few hours? Tangzhong will solve both of those issues.

In previous posts I’ve explained the science of tangzhong, as well as showed you how to apply it to your own favorite yeast recipes. Now, after so many of you have asked, I’m going to see how tangzhong works with both whole wheat and gluten-free loaves.

Let’s start with whole wheat bread and rolls.

“I'm curious how you think this method would work with whole grain bread or rolls? A soft, tender dinner roll with something like 50% whole wheat that stayed moist a day or two would be amazing!” — Maggie, via blog comments

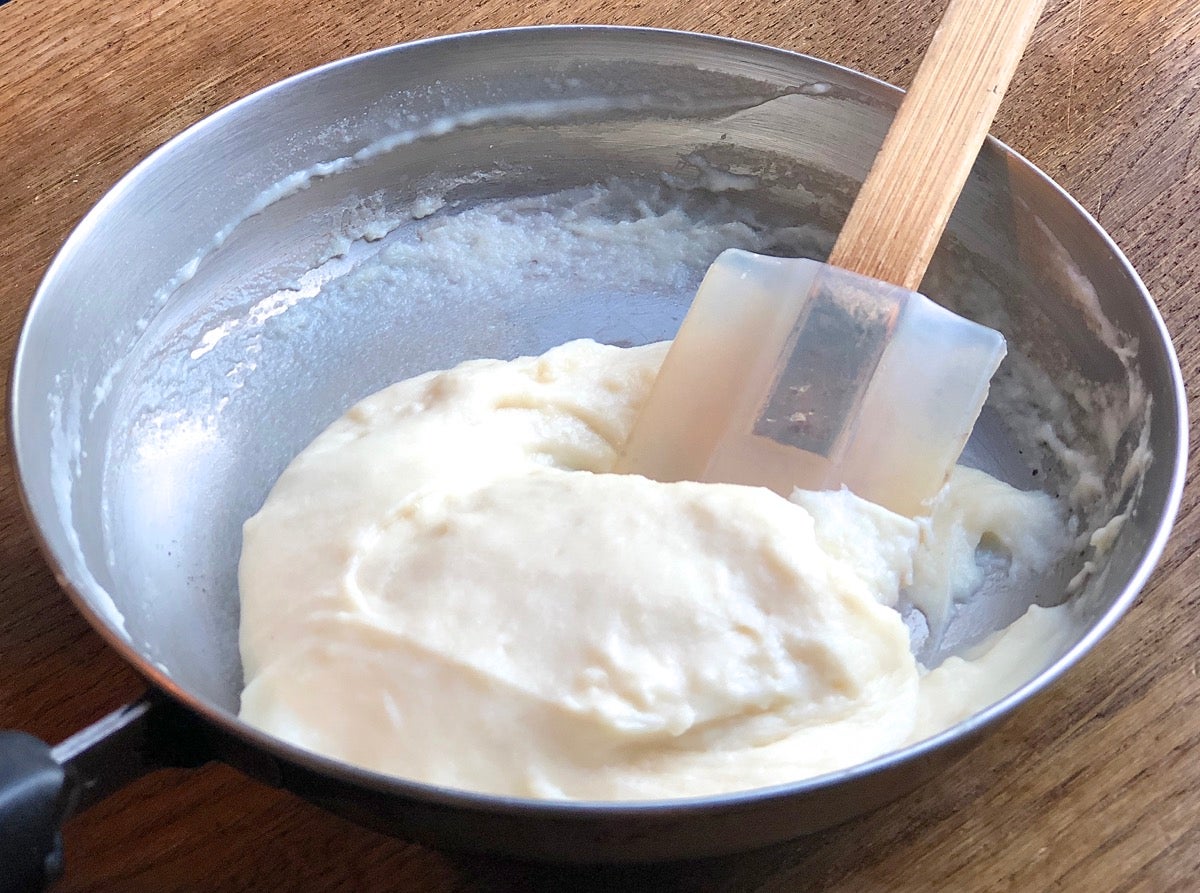

First, a very short explanation of tangzhong (for details, read our introduction to tangzhong). A small part of your yeast bread recipe’s flour and liquid is cooked into a slurry before starting. Typically, tangzhong calls for using about 6% of the flour and 45% of the liquid in the slurry. In a normal-sized sandwich loaf using 3 cups of flour, this translates to 3 tablespoons of the flour and 1/2 cup of the liquid.

This slurry, due to heat-related changes in the starch particles, holds onto its liquid a great deal more effectively than ingredients mixed in the regular manner. The slurry distributes itself throughout the dough during kneading, and once baked helps keep the bread soft and fresh.

Now there’s not nearly as much starch in a cup of whole grain flour as there is in all-purpose flour; whole wheat includes bran and germ along with its starch, while all-purpose flour is mostly starch.

Given its diminished starch, will tangzhong work with whole wheat flour, yielding softer, more storage-friendly bread?

Let's find out.

I make one of our most popular bread recipes, Classic 100% Whole Wheat Bread. I start with my 6% slurry; despite its lesser amount of starch, the slurry made with whole wheat cooks up just fine.

Since I'm using a slurry, which basically holds onto its liquid during the kneading process, I increase the water in the recipe by 2 tablespoons in order to keep the dough nice and soft.

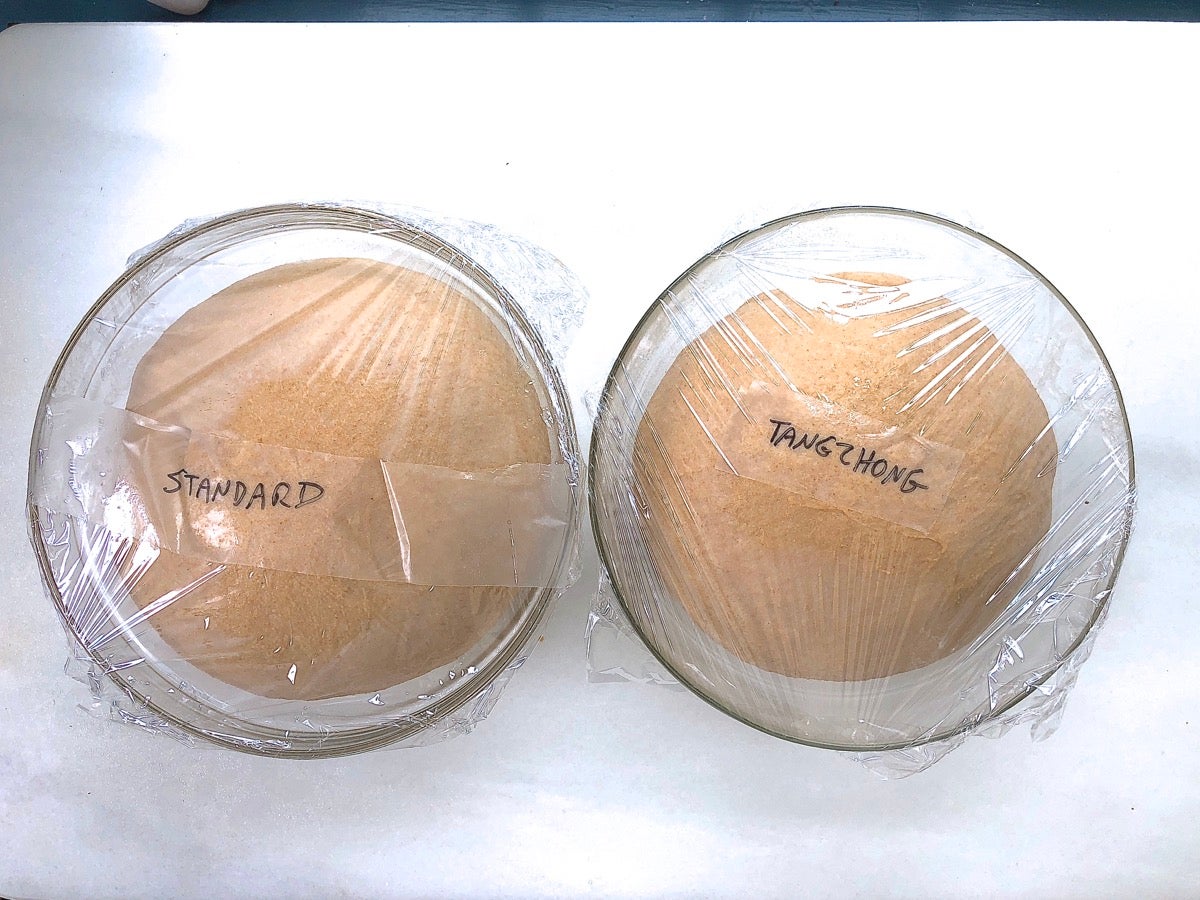

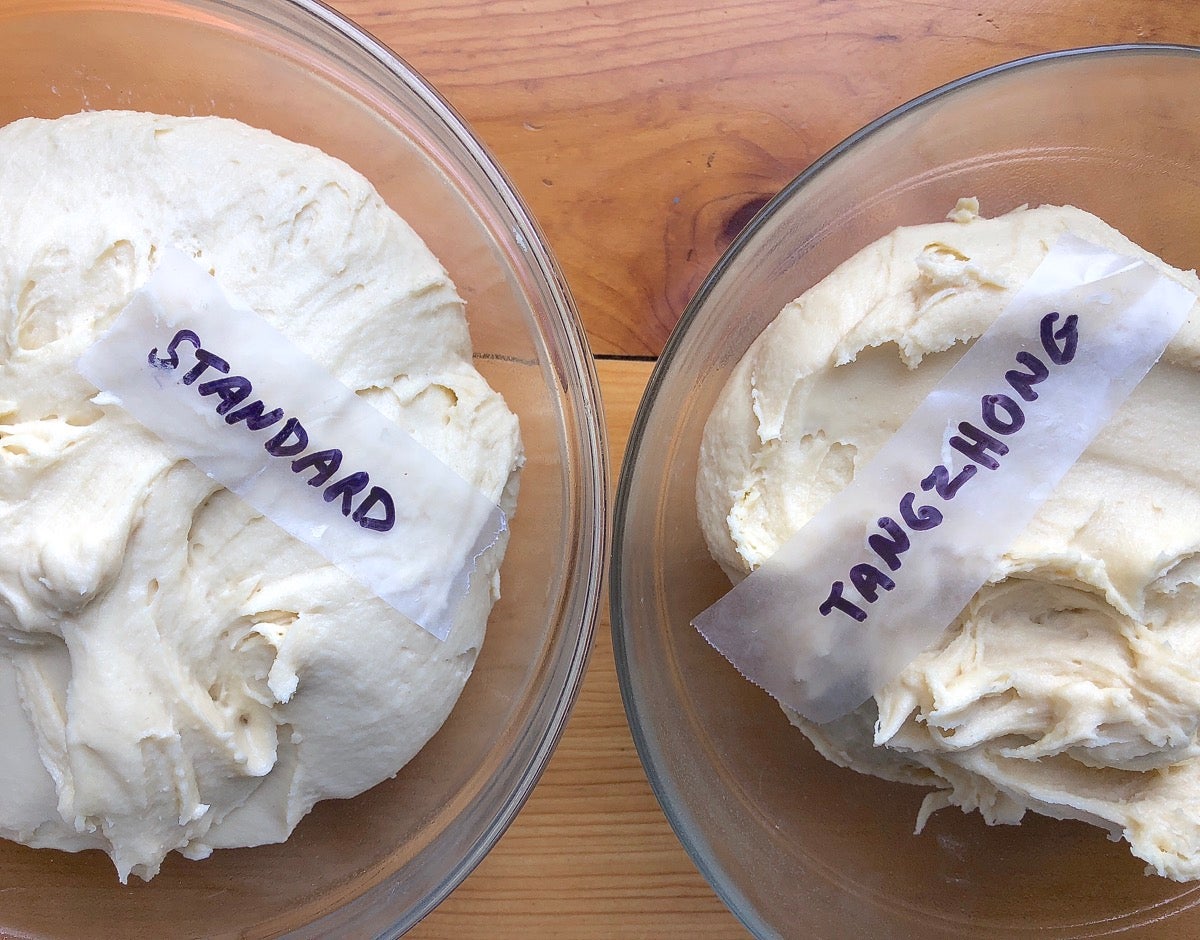

The doughs look identical. They rise at the same rate.

And at the end of the day (literally!) they bake up the same: two gorgeous loaves of 100% whole wheat bread.

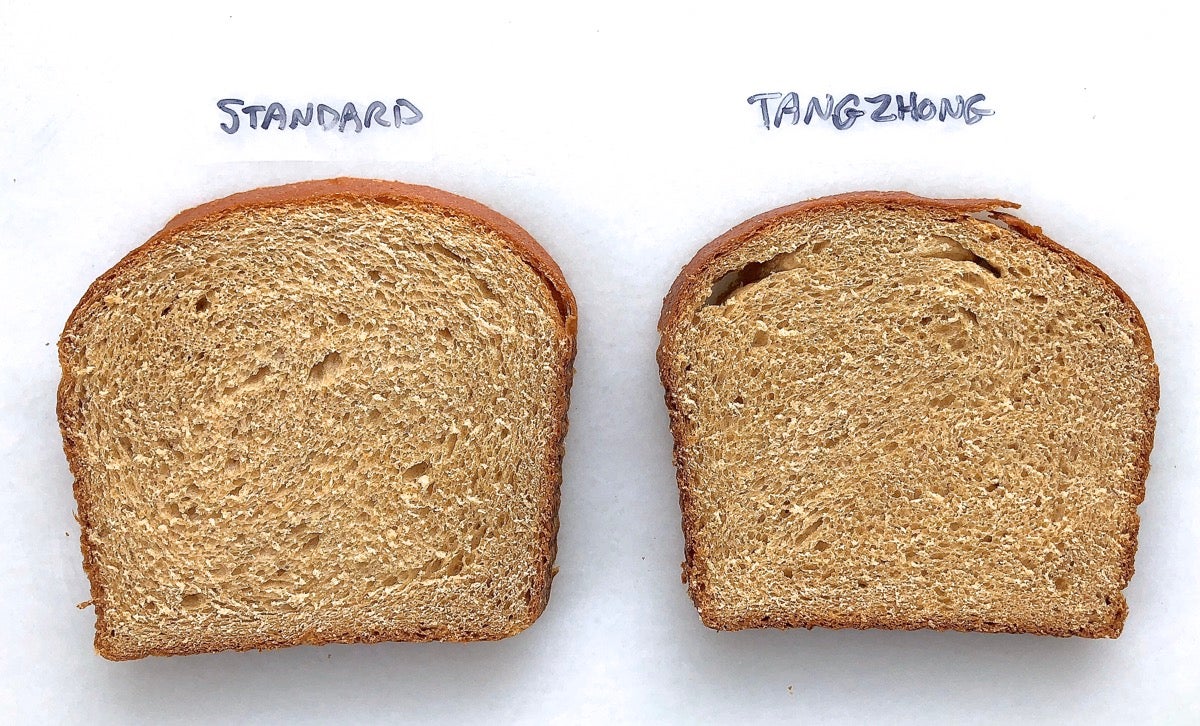

Once cut, the two loaves still exhibit identical features: same interior crumb, same moistness, same sliceability.

So let's get back to our initial question: "Will tangzhong work with whole wheat flour, yielding softer, more storage-friendly bread?

The answer is no. And yes.

Perhaps it's just that the particular recipe I chose to test already makes a soft, moist loaf, but I can't see or taste any difference in the tangzhong vs. standard versions — right out of the oven, or overnight. So that's the "no."

And the "yes"? Two days later, the tangzhong loaf is softer and moister than the standard loaf. So in this particular recipe, tangzhong helps with shelf life.

And in other recipes, those that produce a naturally drier bread, tangzhong will probably encourage some additional fresh-baked softness, too.

Remember Maggie's initial comment? "A soft, tender dinner roll with something like 50% whole wheat that stayed moist a day or two would be amazing!”

Let's give our Dutch Oven Dinner Rolls a try.

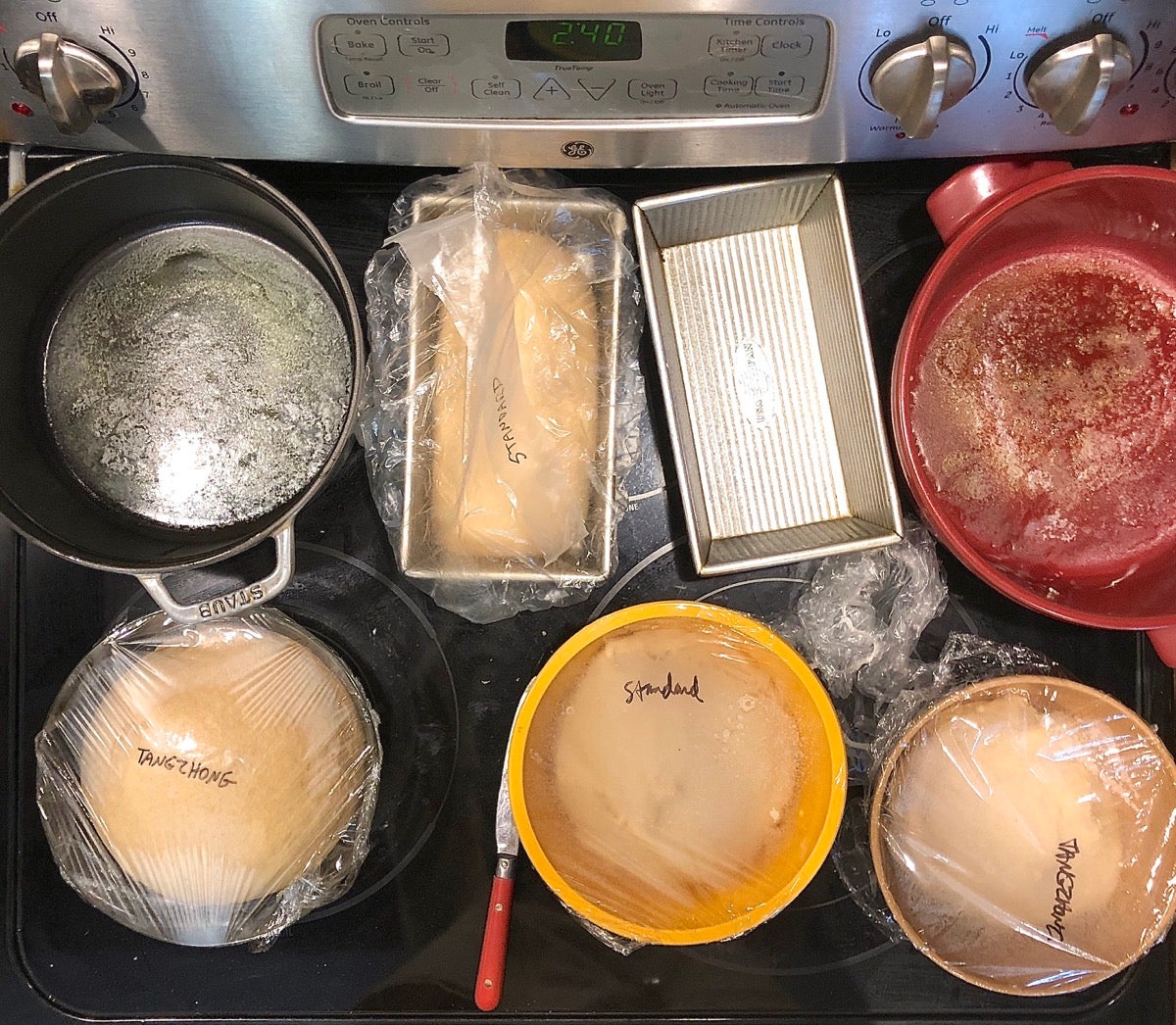

The dough for these rolls is made with 50% golden whole wheat flour, 50% unbleached all-purpose flour. I make the slurry from the whole wheat flour.

And just as with the 100% whole wheat bread above, the dough for both versions is seemingly identical. Soft and quite sticky initially, once it's risen the dough is easy to work with and shape.

Both doughs rise nicely, filling their respective Dutch ovens: the tangzhong rolls in their stoneware pot, the standard rolls in enameled cast iron.

Both bake into beautiful golden rolls. The rolls bake more quickly in cast iron than stoneware, understandably, but I make sure both sets reach an internal temperature of 190°F for a fair comparison.

(By the way, this is a dynamite recipe; I recommend you give it a trial run before Thanksgiving.)

And what about their texture?

Right out of the oven, both sets of rolls are equally soft and moist — pull-apart rolls at their very best.

Three days later, though, the standard (non-tangzhong) rolls are starting to become just a tiny bit crumb-y; while the tangzhong rolls are still just as soft as the day I baked them.

So once again, tangzhong helps with shelf life, if not with initial softness.

Ah, gluten-free yeast bread — the Holy Grail of gluten-free bakers everywhere! Unlike brownies, cookies, muffins, and a number of other treats that can easily transition to gluten-free simply by substituting our Gluten-Free Measure for Measure Flour for any regular flour in the recipe, yeast bread is more complicated.

Think about it: it's a culinary oxymoron. Gluten is what makes yeast bread rise; it's the keystone of any loaf. So gluten-free yeast bread? It's like saying, "I'll have a hot fudge sundae, but hold the hot fudge."

Still, those of us baking gluten-free soldier on, perpetually in search of GF yeast bread that's a dead ringer for our favorite homemade toasting bread. Maybe tangzhong can help prevent two notable downsides of gluten-free bread: its crumbliness and short shelf life.

Let's bake Gluten-Free Sandwich Bread using tangzhong and see what happens.

I start with the slurry: as usual, I use 6% of the flour and 45% of the liquid in the recipe (which in this case is milk).

The slurry cooks up fine.

Next I make two doughs: one following the recipe as written (standard), one using the slurry (tangzhong).

They appear identical; they rise at the same rate.

A couple of hours later — bread!

And here's the question of the day: Will the tangzhong loaf be softer and less crumbly? Will it resist becoming stale as quickly as the standard loaf?

The answer is no on both counts.

Right out of the oven the loaves are identical in all respects: rise, interior texture, sliceability.

As time passes, they "stale" at the same rate; while still good for toast, they've lost that just-baked freshness. So tangzhong doesn't seem to make any appreciable difference in gluten-free bread's texture or shelf life.

That said, I've only tested tangzhong with this single recipe. If you'd like to try tangzhong in your favorite recipe, read our post — How to convert a bread recipe to tangzhong — then have at it!

Meanwhile, if you're into whole wheat yeast rolls or bread, tangzhong can be a definite step up, especially when it comes to shelf life. And after all, who wouldn't love to make their Thanksgiving dinner rolls two or three days ahead of time — with no drop-off in quality?

Read more about tangzhong:

Introduction to tangzhong

How to convert a bread recipe to tangzhong

Have you tried tangzhong yet? If not, here's a great place to start: Soft Cinnamon Rolls. Let us know what you think!