Tangzhong, an Asian technique designed to enhance the softness of yeast bread and extend its shelf life, is being embraced by a small but growing number of bakers. Over the past year we’ve covered the various uses of tangzhong in this blog. Yes, tangzhong is the key to softer sandwich loaves and dinner rolls with better freshness. Yes, it works with whole grains; and you can apply it to most of your favorite yeast recipes, once you understand how it works.

But what about tangzhong in sourdough bread? Does it give the typical sourdough loaf a softer crumb, and allow you to enjoy fresh-tasting bread for days longer?

First of all, let's take a step back and think about this. Many sourdough breads are crusty and chewy; that's a large part of their allure. Do you really want to use tangzhong to soften them up?

Also sourdough breads, particularly those naturally leavened (without commercial yeast), already have an incredibly long shelf life. How much use would it be for tangzhong to potentially extend that shelf life from, say, 10 days to 12? To me, it sounds like using tangzhong in sourdough bread might be a case of carrying coals to Newcastle.

Still, enough of you have asked about tangzhong and sourdough that it was worth trying. And based on my week of experimenting with three different sourdough bread recipes, I can safely say that tangzhong made no difference in the texture of those breads: the soft rolls weren't any softer, and the crusty bread remained crusty. In addition, tangzhong didn't extend the shelf life of any of the breads I tested.

You may want to stop reading right here; the question’s been answered. But if you’re interested in the details of my experiments — and why I believe tangzhong doesn’t seem to produce any effect in sourdough bread — read on.

The recipes I choose to test are Buttery Sourdough Buns, enriched with butter, sugar, and egg; Basic Sourdough Bread, a “lean” (no fat) yet fairly soft sandwich loaf; and Naturally Leavened Sourdough Bread, a crusty artisan-style loaf baked without commercial yeast.

If you aren’t familiar with tangzhong, I highly recommend reading our Introduction to tangzhong. In the meantime, here’s the short version: Tangzhong involves cooking a small percentage of the flour and liquid (water or milk) in a yeast recipe very briefly before combining the resulting thick slurry with the remaining ingredients.

This cooking encourages the starch in flour to absorb more liquid, which it subsequently holds onto throughout baking and cooling. The result? Bread with more moisture, which translates to a softer crumb and longer shelf life.

To start, I need to get my refrigerated starter up to snuff. A couple of feeds and it’s bubbling nicely.

Next, I make dough the standard way, not using tangzhong. The dough is soft but not sticky — see how it clings to the side of the bowl?

Then I start my tangzhong loaf by cooking up a flour/water slurry, using part of the flour and water in the recipe.

Once the slurry cools slightly, I combine it with the remaining dough ingredients to make a soft dough almost identical to the original non-tangzhong dough.

This takes a bit of tweaking with the amount of water. Since the slurry absorbs some of the liquid in the recipe, it’s usually necessary to increase the liquid overall to maintain a soft dough — which is what I did, adding a couple of tablespoons additional water (more on that later).

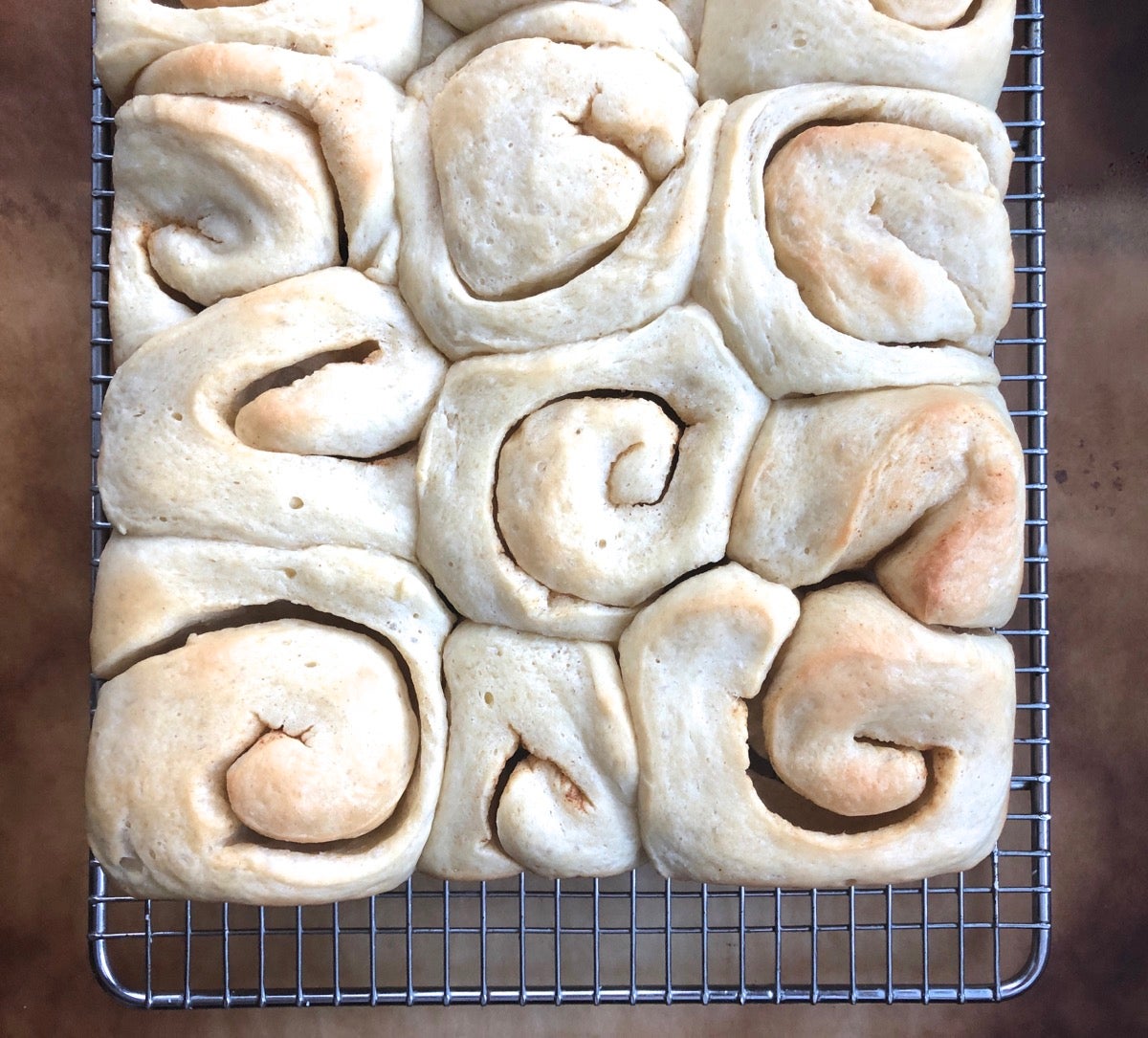

I let the two doughs rise, shape them into buns (with a buttery swirl), let them rise in the pan, then bake.

The finished buns aren’t very brown; I want them to remain soft, so I underbake them just a tiny bit. Despite their rather wan appearance, they’re richly flavored, with a noticeable hint of sour overlaid with butter’s distinct richness.

Once they’re cool, I taste a bun from each batch. Both are equally tender and moist.

I wait a few days, taste-test again. Same result.

At the one-week mark, both batches of buns are remarkably fresh-tasting. It’s not until day 10 that I start to notice some dryness. But throughout, I can detect no difference between the texture of the standard vs. tangzhong buns.

This sandwich bread recipe calls for 2 cups of sourdough starter, double the amount I'd typically use for the single loaf this produces. Let's see what happens.

In order to create the 4 cups of starter I'll need (2 cups for the standard loaf, 2 cups for the tangzhong version), I build the starter's volume over the course of a couple of days. That means transferring it to my Big Green Bowl. (I know each one of you has a favorite big bowl; this fluorescent melamine monster is mine.)

I let the doughs rise, shape them into loaves, and place them in pans.

A couple of hours later — bread! That's the tangzhong loaf in front, the standard loaf behind.

Admittedly not the most beautiful loaves I've ever crafted, they're nonetheless quite tasty: crusty on the outside, moist within, with an interesting "springy," sponge-like texture. This is due to the lack of fat; I wanted to see if sourdough bread made from a lean dough (no added fat) would benefit from the tangzhong treatment.

Again, I taste the bread the day it's baked, then at subsequent intervals up to 10 days.

And again, much as I want to (I love my tangzhong!), I can never detect any difference in texture.

For my last test, I choose a recipe without any added yeast. Including just sourdough starter, all-purpose and whole wheat flours, water, and salt, this bread at its best is crusty, chewy, and riddled with irregular holes.

I make the dough; that's standard dough on the left, tangzhong-enhanced on the right. Again, notice how similar their texture.

The recipe makes two large loaves, but I decide instead to make one loaf and five sub rolls from each batch of dough.

I wonder if this simplest of doughs — just flour, water, and salt — will be the one that finally responds to tangzhong? Will the tangzhong loaf lose its crust, becoming totally soft? Will the tangzhong technique produce a loaf that remains crusty, but stays fresh-tasing longer?

The answer is "Hate to disappoint you, tangzhong fans, but no." The rolls are indistinguishable from one another during the 10 days it takes them to become stale.

Ditto the loaves. Which isn't to say they aren't yummy. My houseful of holiday company is happy to enjoy sourdough bread sandwiches to their hearts' delight!

So there you have it: sourdough bread doesn't appear to derive any benefit from using tangzhong. Which speaks to its inherent "good nature" — sourdough bread's softness (where appropriate) and shelf life are fine as is.

The rest of the story

Remember I said I'd get back to how and why you should adjust the liquid content of tangzhong dough? Here we go.

When using tangzhong, it’s important to keep dough consistency as close as possible to the original. Since the slurry absorbs some of the liquid in the recipe, it’s usually necessary to increase the liquid overall to maintain a soft dough. From past experience with converting standard and whole grain bread recipes to tangzhong, I shoot for dough with overall hydration (including the tangzhong) of about 75%.

Let's use the Buttery Sourdough Buns as an example. Since their original hydration is 60%, during my first test I increase the amount of water in the dough to bring it up to the desired 75% — and end up with a sticky mess.

I try another batch, increasing the hydration to 67% (midway between the recipe's original 60% and my usual 75%) — and wind up with a lovely, soft-but-not-sticky dough.

What happened? Why isn't my usual 75% hydration working with sourdough bread?

The answer, I suspect, is that as fed starter bubbles and grows it produces alcohol — which means the starter’s no longer exactly half liquid and half flour, but starting to edge towards more liquid. This little bit of extra unaccounted for liquid throws off my hydration calculations.

It stands to reason this will always be an issue as far as figuring hydration in sourdough bread goes. The flour/liquid balance of any starter is variable, and also subject to change; some starters are thin to begin with, others thick, and all will evolve once they’re fed.

OK, even though my tests haven't yielded any improvement using tangzhong in sourdough, you're probably going to want to try it yourself. So what’s the best way to figure out how much liquid to use in your tangzhong sourdough bread?

It's simple: Ignore any hydration calculations. Make tangzhong dough starting with the amount of liquid in the original recipe. Then adjust its consistency by eye: As you mix the dough, note how dry it seems. If it’s nice and soft, there’s no need to add more water. If it seems dry, dribble in enough water to make a soft (but not sticky) dough. That’s it; no math!

So why isn't tangzhong a good fit with sourdough?

Jeffrey Hamelman, long-time King Arthur Flour baker and author of the seminal Bread: A Baker's Book of Techniques and Recipes, has the answer, which I've reworded as follows:

The acidity of sourdough bread is a natural shelf-life enhancer. “Starch retrogradation” is the tendency of the starch in baked bread to gradually release any liquid originally absorbed during the mixing and kneading process. This loss of liquid is perceived as the bread becoming stale. In sourdough bread, acidity slows this chemical process; and thus sourdough bread remains fresh (read: with a soft interior crumb) longer than standard bread.

They say you can't make a good thing better. And in the case of tangzhong in sourdough, I guess that's the truth.

Read more about tangzhong:

Introduction to tangzhong

How to convert a bread recipe to tangzhong

Tangzhong beyond white bread: Will it work in whole wheat and gluten-free breads?

Want to learn more about sourdough baking? Check out The Complete Guide: Baking with Sourdough.